26.09.2025

A Glance in the Rear-View Mirror – The 1970’s

My Career Officially Begins in the Family Business

Introduction:

I’ll continue along the same path as before, sharing my memories and reflections from three perspectives:

– Our company and my own career

– The transport industry

– Society

It’s Official Now

Hello again. We’re now entering the 1970s – the decade when I truly became part of the business.

For me, joining our family company felt like Christmas had come early. Ever since the late 1950s I had known, without a shadow of doubt, that this was exactly what I wanted to do.

I threw myself into the work with enormous enthusiasm and energy. It felt as though the opportunities ahead were boundless. In fact, I had made up my mind as early as the age of five. It was a Saturday morning Dad arrived home with a brand-new Köln Ford truck, and I got to sit behind the wheel to admire it. It was then and there that I decided that this was what I would devote my future to.

Even at that young age I had ideas and visions about where the company could go. I also discovered a clever way of making sure my thoughts were heard. The most effective route was through Mum. She had a knack for persuasion and could often convince Dad of the merits of my ideas. As it happened, hers and mine often matched.

My Career Before Officially Joining the Family Business

Let us return to my work history in the early 1970s. Before I had a driving license, I worked at my uncle Leif’s gas station. Leif and Leila Sundholm operated the Union station in central Kokkola, which was the city’s largest and most modern at the time. There were in fact, many gas stations back then – and on Långbrogatan alone there were four. Competition was driven by who offered the best service. Our work as gas station attendants involved a wide range of tasks. Besides tanking up cars, we washed windows, checked engine oil, topped up washer fluid, tested tire pressure and more.

Where I learned the meaning of customer service.

We also provided full car servicing, including oil changes for the engine, gearbox, and propeller shaft. Back then, the undercarriage also required lubrication, as each moving part had its own grease nipple. Our station was the only one equipped with an automatic car wash. This meant that, on Saturdays for example, we could wash up to 100 cars in a day.

I would say that my time at Leif’s gas station gave me a very clear understanding of what customer service really means. It is an insight that has benefited me throughout my career.

Starting Out as a Driver for Dad

I got my driving license in September 1972. I turned 18 on 18 June, but because I had been caught driving a little “ahead of time”, the license was delayed until 18 September. That timing was a bit unfortunate. On 1 July a new regulation came into force, replacing the old professional license with a new system of lettered categories. The former professional license was converted into ABCE, with the E corresponding to the old qualification. According to the new laws, anyone who had been granted a truck license before 1 July 1972 was automatically upgraded to ABCE. Since I received mine in September, I missed out and had to wait until 1975, when I turned 21. It was not too great a setback, as I was doing my military service from February 1974 to January 1975.

By the early 1970s our business had grown strongly. We were operating four tankers for Oy Union-Öljyt Ab, and this was a very profitable line of work. Personally, though, I was not particularly interested in driving fuel out to the countryside. In addition to the tankers, we had an old two-axle Bedford truck for gravel transport. That was the vehicle I started my driving career with.

A new, fine rig from 1970, the Scania LBS 110. The truck was equipped with an ARP mobile phone.

In January 1973, I received my first brand-new truck – a Scania LS 110. It was an excellent and efficient vehicle, and it was really something to be entrusted with something like that at just 18 years old. At first, I drove routes for Lastbilscentralen KTK in Kokkola.

Interesting People and Contacts

Already in the spring, Dad and I travelled to Åland to purchase a trailer so that we could start with long-distance freight. I remember the trip well, and the events surrounding the purchase from the businessman Rafael Mattson in Mariehamn.

Among other things, Rafael told us that he had bought his very first shares in Viking Line (then SF-Line). He would later become one of the shipping company’s largest owners.

Another detail I recall is that Rafael took us on a short drive around Mariehamn. We passed an apartment building with a small car dealership on the ground floor selling Mercedes passenger cars. I remember Rafael pointing it out and saying that the owner was a very skilled businessman. “He will go far in the future,” he said. The dealership was owned by none other than the highly successful Anders Wiklöf.

During 1973 we still had four tankers and that business was going very well. But together with Dad we also began to build up freight transport, using the one truck we had that could handle both gravel and cargo. This was the year the foundations of today’s Ahola Transport’s international freight operations were laid, when we made our very first trip to Sweden.

Conscription

In February 1974 I began my military service with Pohjanmaan Tykistörykmentti in Oulu. After basic training I was appointed as a driver, with a service time of 11 months. I was discharged in January 1975. Serving in the Finnish army was an interesting and valuable experience. There were still a few regulars who had seen action in the wars, which added a certain edge to my conscription period.

Now It Got Serious

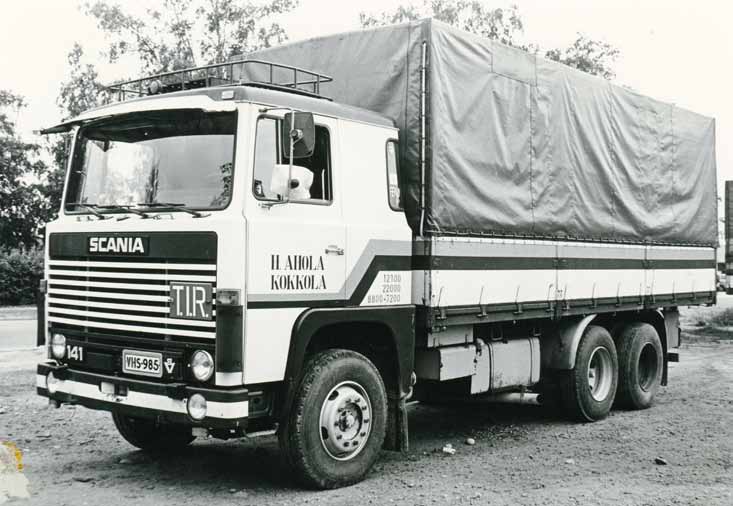

My ambition was for the company to grow in long-distance freight, resulting in Dad investing in a brand-new Scania LS 141. Both the truck and its trailer were fitted with tippers to make them as versatile as possible. The trailer was a Teijo, manufactured at Teijo Manor. The truck was also equipped with an ARP mobile phone. Dad handed me the keys and said: “Here’s the truck and the phone — now find the work yourself.” Though partly said in jest, the message was clear: it was time for me to take responsibility. That trust gave me a strong sense of self-confidence, and it marked a real step in building up the business.

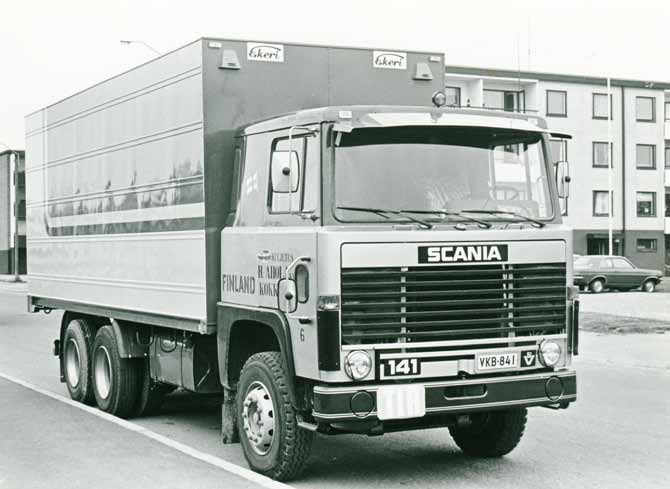

Scania LBS 141, 1979 model year

At first, we handled both domestic and international transport, though during the first year it was mainly within Finland. Much of it was bulk cargo, especially agricultural products such as feed and fertilizer. At the time, most unloading was done by hand, and on a busy day we could end up manually shifting as much as 50 tons of sacks. The advantage, of course, was that there was no need for the gym in the evenings. The work provided all the exercise I needed. It was both useful and enjoyable. My brothers Lars, Nils and Rolf were a great help in distributing feed and fertilizer to the countryside. Soon after school my brothers were tasked with coming along to help with unloading. It was a great help to have them on the platform, pushing the sacks to the edge.

In 1976 the truck was fitted with a so-called TIR tilt to enable international transport. This was before the EU, when all goods had to be cleared through customs, even within the Nordic region. In the 1970s the fur farming industry was a major force in Ostrobothnia. Raw materials for feed came mainly from Northern Norway in the form of fish waste from processing plants. My first fish transport took place early in 1976, when I collected a load from Honningsvåg in Finnmark. It was a memorable trip with shifting weather, dramatic scenery and demanding road conditions. The customer for these transports was Finnjak feed factories.

The customs station at Svinesund between Sweden and Norway in 1979.

Despite relatively high inflation, profitability during the decade was very strong. Looking back at the figures from that time, the operating margin could be around 40 percent. The downside was corporate taxation, which was progressive and could reach as high as 60 percent.

My friend Bo-Håkan Simell and I were in Sarpsborg, Norway, on our way to Løkken in Jutland to pick up a cargo of fish.

Even so, the 1970s turned out well for our company. In 1976 Finland’s Fjärrexpress (Oy Suomen Kaukokiito Ab) also became a partner of ours. This was made easier by the fact that Dad was good friends with the managing director of its international transport division.

Scania LBS 141, 1979 model year

The fur industry in Ostrobothnia was exceptionally strong during this period and provided a great deal of work for the transport sector. The largest player was Ostrobotnia Päls, which acted as importer and wholesaler for the industry.

The company also owned other businesses, such as Iskalotten and Kalottspedition. Iskalotten would later become a key partner for Ahola Transport – something I’ll return to in the next chapter, when I cover the 1980s.

Back then, we carried out most of the service and maintenance ourselves in our own premises. At the end of the 1960s Dad bought an old cowshed, which we converted into a service hall. We could fit in four tractor units at once, which covered our needs well.

I spent countless hours there keeping the vehicles in good condition. Perhaps even a little too many. At one point I realized that my friends had grown tired of asking me to join them in shared activities. It was a wake-up call, and I wanted to rebuild those friendships. It took some time, of course, but eventually I managed to restore those relationships.

Most of the time, I naturally worked as a driver. It was enjoyable and rewarding, but I soon realized I wanted something more. For an extrovert, sitting alone in a truck is not the easiest. My plans always revolved around looking ahead and developing the business.

There was one thing, however, that weighed heavily on my mind during the second half of the 1970s. Dad began speaking about not being around for much longer. He seemed to have a strong sense about it and wanted to prepare me for what might come.

Perhaps as part of that preparation, I became a co-owner of the company in 1977. A few years later he encouraged me to buy into a larger share, which I did.

Although the business was profitable, it was extremely difficult to strengthen our equity. The reason was the harsh taxation, which could take up to 60 per cent of the profits. This made future challenges difficult to meet. I will return to this in the next chapter.

My Wife, Tiina Niemi

As for my private life, I started seeing my future wife, Tiina Niemi, in 1978. Tiina was then 18 years old and in her final year of upper secondary school. During the study leave before her matriculation exams she joined me on a few “fish trips” to Northern Norway, which was of course very pleasant for me.

The 1970s, trucks didn’t have microwaves and Tiina prepared food and coffee on a Primus stove. This was during a trip when we picked up fish from Northern Norway in the spring of 1978.

My Wife, Tiina Niemi

Camping

We married straight after the exams, on 16 June 1979. That autumn, Tiina began her nursing studies. At the same time, she also started helping with administrative tasks such as invoicing, which my mother had handled earlier. I remember how delighted we were the first time our monthly turnover reached FIM 500,000.

Scania LBS 141 for fish transport from Northern Norway

Tiina handled invoicing alongside her studies. The precision required in nursing suited certain tasks in the company very well, such as breaking down and compiling costs and turnover. To give me a simple overview of the figures behind our work, Tiina was tasked with calculating all income and expenses right down to the mark and penny per kilometer. This way I could clearly see the operating margin. It also gave us the basis for simulating the development of the business. This was Tiina’s area of expertise, and I could rely completely on her figures. Over the years the method has developed into a way of managing the company with real-time data and information. Today we call this “tiedolla johtaminen” (data-driven or knowledge-based management), an expression that sounds much clearer in Finnish than in any other language.

Tiina soon proved to be a tremendous asset to the company, eventually becoming its very first office employee. She laid the foundation for rigorous follow-ups and sound administration.

It was a very happy time for us as newlyweds, building our life together. Back then we started modestly, renting our first home and buying a little furniture. If I remember correctly, we spent FIM 1,000, around EUR 168, on a kitchen table, a second-hand bed and a transport-damaged bookcase. But we were very happy to begin our life together. A heartfelt thank you to my beloved wife Tiina. She has been a wonderful sounding board for me and has helped me to think differently and see things from new perspectives.

Picking up a load of fish from Vadsø in Norway together with my girlfriend Tiina.

The Next Step in Our Development

At this point it became important to consider the next step in our development. I realized that we needed more direct customers and to be less dependent on freight forwarders.

It soon became clear to me that driving for forwarders didn’t offer much room to improve the efficiency of the business. We eventually ended our cooperation with Kaukokiito and shifted our focus toward building a direct customer base. When we began looking for new opportunities, it was only natural to turn towards the fur industry. In the beginning, we secured our own export loads, and the return cargo was often for different customers within fur farming. During this period the procurement channels were quite concentrated and were limited to just a few players. The largest was Ostrobotnia Päls, through which Kalottspedition exercised strong control over the market. In addition, there were a few smaller wholesalers who imported raw materials from across the Nordic region, though mainly from Northern Norway. This situation limited the development of logistics within the fur industry for around ten years to come. I will return to this again in the next chapter. Towards the end of the 1970s we invested in several new units, driven by strong faith in the future.

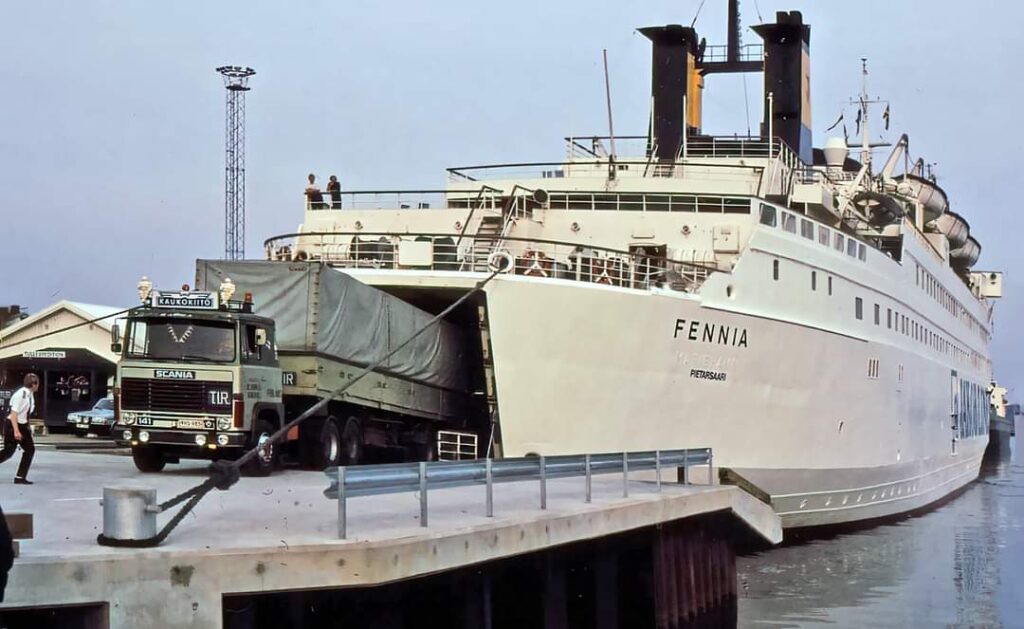

M/S Fennia operated on the Vasa–Sundsvall route. Here we are coming from Trondheim.

Demanding, yet rewarding

Our first years together with Tiina were very much work-centered. I drove full time, mostly to Northern Norway, which meant I was rarely at home. At that time, it was not unusual to make two, sometimes even three, trips to Norway in a week.

Dad

What Dad had hinted at earlier about his health gradually began to show. He was often very tired and no longer had the strength to work as he once did. Mom tried to persuade him to see a doctor to find out the cause of his fatigue, but Dad held back, perhaps not wanting to hear what it might be.

One joyful highlight was that Mom and Dad fulfilled their long-held dream of traveling to the United States. The opportunity came when the Laestadians organized a group trip to Washington State – a destination that suited Dad perfectly, as several of his cousins lived in the Seattle area. That journey meant a great deal to both, and we were truly happy they got to experience it. That summer, Tiina and I took care of the business, with generous help from my brothers.

Overall, I remember the 1970s with warmth and happiness.

Society

Like the other post-war decades, the 1970s too were marked by strong faith in the future and a sense of optimism.

My own memories of the decade are also very positive when it comes to social development, even though there were aspects I could not embrace, and which did not align with my own values. This was the so-called “Finlandization” and the Marxist and communist ideology that had a strong presence in the 1970s.

Seen from today’s perspective, it is almost comical how Finland bowed towards the Soviet Union, and how it was entirely impossible to voice any form of criticism in that direction. Urho Kekkonen was re-elected president of Finland in 1974 with the help of a special law, the so-called “Kekkonen Act”. This constitutional change allowed him to stand for a fourth term without a general election, as the amendment gave him the right to continue in office. He was formally re-elected in 1974, which gave him yet another mandate.

With the support of the Soviet leadership, Kekkonen succeeded in making himself indispensable.

More broadly, Finnish politics in the 1970s were characterized by bloc politics between the Social Democrats (SDP), the Centre Party (Keskusta) and the Finnish People’s Democratic League (SKDL), dominated by the communists, while the National Coalition Party (Kokoomus) almost always remained outside government. President Kekkonen played a decisive role in determining which parties could form a government, always with an eye to relations with the Soviet Union.

Prime Ministers and Other Prominent Leaders

- Rafael Paasio (SDP) – Prime Minister briefly from 1966 to 1968 and a central Social Democrat also in the early 1970s.

- Teuvo Aura (Liberal) – Led two caretaker governments in 1970 and 1971–72.

- Ahti Karjalainen (Centre Party) – Prime Minister in 1962–63 and 1970–71, important in foreign policy as a close associate of Kekkonen.

- Kalevi Sorsa (SDP) – One of the most influential Social Democrats, Prime Minister from 1972 to 1975 and several more times later.

- Martti Miettunen (Centre Party) – Prime Minister in 1961–62 and 1975–77, a loyal supporter of Kekkonen.

- Kalevi Kivistö (Finnish People’s Democratic League) – A key left-wing politician and Minister of Education during the 1970s.

- Paavo Väyrynen (Centre Party) – Began his long career in national politics in the 1970s, serving as Foreign Minister from 1977.

- Harri Holkeri (National Coalition Party) – Emerged during the decade as one of the leading figures in the conservative party.

Ahola Transport’s First International Transport and the Oil Crisis of 1973

The positive economic trend continued in line with the broader post-war development. Below are a few reflections that echo the progress seen in the 1950s and 1960s. But one major event that shaped the 1970s was the oil crisis of 1973. Since officially entering the transport industry in the early 1970s, I can say that my career of more than 50 years has included quite a number of global crises. The first of these was the oil crisis of 1973. I have vivid personal memories of that day.

My father Helge and I were in Sweden at the time, carrying out what would become Ahola Transport’s very first international transport. The load was zinc from Outokumpu’s factories in Karleby (Gamlakarleby) to Söråker, just outside Sundsvall. For the return journey we carried components and machinery for Rukka Ab in Karleby. The oil crisis erupted during this very trip, in fact as we began our journey home. What made it so unsettling was that society was plunged into darkness both in Sweden and in Finland. Streetlights and advertising signs were switched off, creating an eerie, almost apocalyptic atmosphere. On top of that, nearly all petrol stations were closed as people had been hoarding fuel. Fortunately, we managed to refuel Kemi, which allowed us to make it home.

What Triggered the Oil Crisis?

The oil crisis of 1973 – also known as the first oil crisis – was caused primarily by political conflict in the Middle East, namely the Yom Kippur War in October 1973.

Timeline of Events

- The Yom Kippur War (October 1973)

- Egypt and Syria attacked Israel in an attempt to regain territories lost in the Six-Day War of 1967.

- The United States and several Western countries provided military support to Israel.

- OAPEC’s Response

- In retaliation for Western support of Israel, several Arab oil-exporting countries – members of OAPEC (the Arab bloc within OPEC) – decided to use oil as a political weapon.

- Oil Embargo and Production Cuts

- OAPEC imposed an embargo on the United States, the Netherlands and other countries that supported Israel.

- At the same time, OPEC nations drastically reduced oil production.

- As a result, oil prices quadrupled within just a few months.

Financial Growth and Industrialization (early 1970s)

- Finland entered the 1970s with a relatively strong economy, thanks to rapid industrialization in the 1950s and 1960s.

- Exports – particularly of forestry products such as paper, timber and pulp – remained central to the economy.

- Industrialization continued, with investments in heavy industry, especially in metals and engineering.

- Living standards improved, urbanization increased, and the welfare system was expanded.

- Trade with the Soviet Union mitigated the recession after the oil crisis.

- The years of rapid growth in the early 1970s were followed by an international oil crisis. Between 1974 and 1979 oil prices rose tenfold, leading to global inflation and recession. Internationally, the downturn is seen as having begun in 1973, but in Finland its effects on industrial production were only felt in 1975, when output began to decline. The slowdown was compounded by the free trade agreement signed in 1973 between Finland and the EEC, which exposed Finnish industry to tougher international competition and sharply reduced exports to Western Europe.

- In 1976 and 1977 industrial production showed almost no growth, until output began to rise sharply again in 1978. Growth in 1978 and 1979 was faster than average. This was due to three devaluations of the markka in 1977 and 1978, which together amounted to 19 per cent against foreign currencies. During the oil crisis, the situation in Finnish industry was also eased by bilateral trade with the Soviet Union. Increasingly, industrial goods were exchanged as compensation for the higher price of oil.

- In 1979 the price of oil rose sharply again, triggering a second oil crisis and leading to a global recession at the start of the 1980s The effects were scarcely visible in Finland’s industrial production. The international competitiveness of Finnish industry was maintained in part through two devaluations in 1982, which together raised the value of foreign currencies against the markka by 11 percent. The rise in oil prices associated with the early 1980s oil crisis again boosted exports to the Soviet Union.

- As a result of the oil crisis, the 1980s in Western Europe became a period of weak economic growth. In contrast, Finnish industry performed noticeably better than the European average, from the late 1970s until the end of the 1980s.

The Transport Industry in the 1970s

The major players in the transport industry at the time included, among others:

- Paul Nyholm, probably the largest family-owned transport company in the Nordic region at that time

- Niinivirta Transport

- Kuljetusliike Lauri Vähälä Oy (Kiitolinja)

- Pynnönen Oy (Kaukokiito)

- Ilmari Lehtonen (Kaukokiito)

- Viinikka Oy, bulk and chemical transport

- K. Sarpo, Tanker Transport for Neste

- Saari Oy (Kaukokiito)

- Albert Norrgård (frozen goods transport)

From Sweden and Norway, I also remember some of the major freight forwarders, such as Bilspedition, Autotransit, ASG, Fraktarna, as well as:

- Adamssons Transport, Jönköping

- Börje Jönsson, Helsingborg

- Kingsröd Transport A/S, Sarpsborg

- Björnflaten A/S, Tromsö

Each of these companies was large and successful, and they served as role models for me. Having such role models was important – they inspired the vision I already held: to grow our company into a major force in road transport. I’ve found that having a vision truly pays off: visions have a way of becoming reality. Without them, you risk wandering aimlessly, lacking clear direction.

Statistics on transport capacity in Finland, 1970–1979

| Year | Total number of passenger cars | Trucks | Vans (light trucks) | Buses | Total vehicles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 707 218 | 56 220 | 45 881 | 8 093 | 817 412 |

| 1971 | 748 013 | 66 495 | 46 272 | 8 224 | 869 004 |

| 1972 | 812 634 | 68 032 | 47 167 | 8 339 | 936 172 |

| 1973 | 888 252 | 70 534 | 48 432 | 8 403 | 1 015 621 |

| 1974 | 930 562 | 73 765 | 50 172 | 8 561 | 1 063 064 |

| 1975 | 989 835 | 76 388 | 50 596 | 8 645 | 1 125 090 |

| 1976 | 1 026 293 | 81 049 | 50 586 | 8 813 | 1 166 741 |

| 1977 | 1 068 585 | 85 128 | 49 993 | 8 743 | 1 212 449 |

| 1978 | 1 108 130 | 87 802 | 50 177 | 8 758 | 1 254 867 |

| 1979 | 1 161 948 | 90 451 | 51 447 | 8 797 | 1 312 643 |

Professional haulage accounted for between 25 and 50 percent of the total volume.

Facts About Our Company and About Me in the 1970s

I have not found the annual accounts for every year, but here are some examples.

We had three tankers and one gravel truck (Bedford) in 1972.

Close up of the Robson drive.

The following year our fleet grew with another gravel truck – a Scania LS 110. The vehicle was equipped with a Robson drive, which allowed it to temporarily become tandem-driven in poor conditions. This was achieved by hydraulically pressing a Robson roller between the drive wheels and the bogie axle.

My first real truck for freight transport, a Scania LS 140, here on its way to Oslo. The photo is taken by my good friend Markus Ventin who drove for us in between his theology studies.

In 1975 Dad bought “my” Scania LS 140, a versatile combination. It was a completely new unit with a Teijo tipper trailer, well suited to carrying many different types of freight. “Here’s the truck and the phone — now find the work yourself.” Dad said.

One of the first trips with this rig in the summer of 1975.

In 1977 cooperation with Kaukokiito began, with one vehicle for international transport to Sweden and Norway. I remember one particularly interesting episode. Our neighboring town of Jakobstad had Strenberg’s tobacco factory, which shipped to both Sweden and Norway. On one occasion we loaded a full consignment of tobacco for Oslo, with a cargo value of about FEM 5 million. That was exciting. For some reason there are far fewer tobacco transports today.

| Year | Turnover | Operating profit | % | Net profit | % |

| 1970 | 147503 | 18241 | 12,37 % | ||

| 1971 | 186796 | 12929 | 6,92 % | ||

| 1973 | 205975 | 20637 | 10 % | ||

| 1976 | 510781 | 89622 | 18 % | 61294 | 12% |

| 1977 | 696398 | 147351 | 21 % | 104460 | 15% |

Finally, I want to mention a few people I remember from the early 70s with gratitude and warmth:

Boers Skog

Gustav Finell

Krister Jansson

Bo-Håkan Simell

Carl-Johan Thylin

Karl Johan Kronqvist

Jan Vidberg

Stig Ventjärvi

Helge Snellman

Bjarne Nygård

Yngve Ahlskog

Lars Värnman

Rolf Finne

Leif Sundholm

John Brännkärr

Hans Ahola,

Chairman of the Board

Ahola Group